How Educators Can Use AI to Support Student Growth

13 minute read

KEY TAKEAWAYS

ChatGPT has not led to a cheating epidemic. Rather, student motivation to cheat has remained unchanged.

Educators should be prepared to adapt admissions strategies, lesson plans, and student assessments to the world of AI, encouraging students how to think critically with regard to these tools.

PolyPilot is the first AI-guided research mentorship program built to ethically promote the accessibility of research to students around the world.

(This article is adapted from Polygence’s white paper “From Turing to Teaching Techniques: The Evolution of Artificial Intelligence and How Educators Can Use it to Support Student Growth”)

Since the release of ChatGPT in November 2022, anyone paying attention to the development of AI–which by now is anyone using the internet–can recall a moment that they have been shocked.

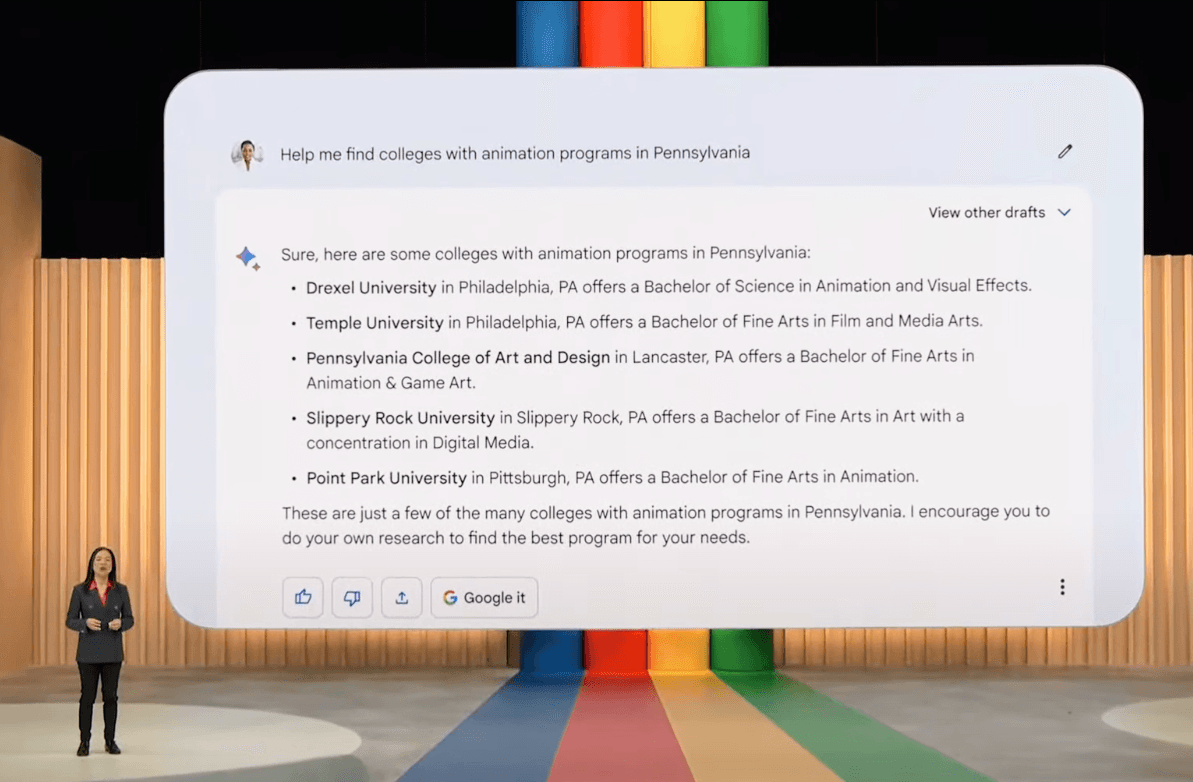

For Emily, an independent college counselor working with students in the Philadelphia area, that moment came in May 2023. That’s when Google released a product demo video of its Bard chatbot, since rebranded as Gemini (LeBourdais, Using Google’s AI, 2023). After a few playful use cases, Sissie Hsiao, Google Vice President in charge of Gemini, turns to another example: she imagines she’s an 18-year-old at the beginning of the college search, using the following question as a prompt:

I'm thinking about colleges, but I'm not sure what I might want to focus on. I'm into video games. What kinds of programs might be interesting?

The chatbot responds with four highly relevant majors and career fields that the student might pursue, including game design, computer science, and animation, as well as brief descriptions of what they entail.

Deciding animation looks pretty interesting, Hsiao reads the next prompt: Help me find colleges with animation programs in Pennsylvania.

The chatbot spits out a targeted list of 5 colleges in Pennsylvania with a game design major.

Next prompt: Show these on a map. Bot plots schools on a Google map.

Prompt: Show these options as a table. Bot creates a table.

Prompt: Add a column showing whether they're public or private schools. Bot adds a public / private column.

Prompt: Move this to google sheets so my family can help me later with my search. Bot does so.

“My mind was blown,” said Emily after watching this video. In under two minutes, the chatbot had compiled a preliminary list of colleges based on specific criteria that even an experienced college counselor may have taken ten times longer to pull together.

Do your own research through Polygence!

Polygence pairs you with an expert mentor in your area of passion. Together, you work to create a high quality research project that is uniquely your own.

From college counselors to medical researchers, from CEOs to copyeditors, people across nearly every profession and job title have had similar “mind blown” moments in the time since this product video. In his new book, Co-Intelligence: Living and Working with AI, University of Pennsylvania Wharton Professor Ethan Mollick estimates it takes at least three sleepless nights to really get to know AI and what it’s capable of. During those nights, certain questions might race through your head: “What will my job be like? What job will my kids be able to do? Is this thing thinking?” (Mollick, 2024, p. xi) Precisely the kind of question that both students and college counselors like Emily may have lay awake thinking about, too.

For many of us, it’s difficult to know where to turn for well-informed answers to those kinds of questions. Lest we become prisoners of the moment, it is important to know how this technology developed, and not just since the launch of ChatGPT.

What follows are excerpts of our recent white paper on AI and education, contextualizing how it relates to teaching, learning, and college preparation. We touch on the origins of AI in the mid-twentieth century, examples of implementation in the education space since that time, and how experts are responding to these developments in their work with students.

Origins of Artificial Intelligence

To begin, how do we define artificial intelligence? Most of us encounter it online through the likes of Claude, Gemini, and OpenAI’s ubiquitous ChatGPT. After witnessing the power of these chatbots, related image and video generators like Midjourney and Sora, and even humanoid robots like Figure01 and Tesla’s Optimus, it’s an easy leap to imagine fully self-aware robots with sinister designs to take over the world. These are theoretical forms of artificial general intelligence (AGI), a kind of AI that would be like a human in every discernable way.

To focus more on science fact than science fiction however, our exploration is constrained to the kind of artificial intelligence we all interact with most frequently: those built on Large Language Models or LLMs, which are algorithmic models trained on immense amounts of data which allow them to understand and generate natural language.

A Crash Course in AI History

A practical starting point for the birth of AI dates to 1935, when Alan Turing, a mathematics student at King’s College, Cambridge, set about to solve the Entscheidungsproblem. Translated as the “decision problem,” it asked whether all mathematical problems with yes-no answers can be solved using a standard “recipe.” This recipe was, in effect, a program: a series of rules that could allow a machine to arrive at a conclusion.

The earliest computing machines that Turing helped to develop could do certain tasks, like complex mathematical equations, that most humans found extremely challenging. But were they just following recipes or actually thinking?

To answer this question, Turing conceived of a series of questions for these programs to determine whether their answers were “indistinguishable” from a human’s. You don’t need to prove things are identical in this test, only that you can’t tell the difference between them. We still refer to this process today as The Turing Test, shorthand for a basic means of determining whether a machine is “intelligent” in the human sense of the word.

By the 1950s, mathematicians and biologists were also turning their attention towards thinking machines and how they might be developed. In fact, a group of leading researchers on these subjects gathered at Dartmouth College in the summer of 1956 to consider this new field of inquiry. The term “AI” was one of the main products of this Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence (DSRPAI).

AI advanced slowly in those early years, largely due to limitations of computer power. But the series of so-called “AI winters” began to thaw in the 2010s, when predictive AI began to transform the way we interpret data with probabilistic models. Internet companies like Amazon began training predictive AI algorithms on its troves of consumer data in order to organize its supply chain more efficiently. The trick was that these models required supervision, meaning the algorithms relied on human programmers to tell them what data was important.

All that changed in 2017, though, when Google researchers published a paper playfully titled “Attention is all you need.” (Vaswani et al., 2017) It proposed a new way for computers to understand human language with “transformers,” coded directions that instructed AI to focus its attention only on the most useful part of a text. Just as students highlight the most salient parts of a textbook, this transformer allowed AI to work with language in ways much more closely aligned with human thought. This development is the core of the predictive text generation that Large Language Models perform today.

The major breakthrough here is that current LLMs do not require the same kind of supervision that earlier forms of AI needed. To return to the “recipe” analogy, imagine a chef experimenting with various ingredients by combining them in a lightning fast process of trial and error. Sooner or later–and the largest models like Google’s Gemini or ChatGPT take months and hundreds of millions of dollars of computation to pretrain in this messy pantry of hundreds of billions of ingredients or “parameters”–their iterations eventually reveal that apples and cinnamon go well together.

How AI is Changing Education

Few technologies have disrupted the education space so quickly as AI, and even fewer have raised more questions so urgently. This has led to existential questions about the nature of education. If ChatGPT can write an essay for students, for instance, is it more important that they write the essay themselves or for them to learn the prompts that will create those essays? Within this question sit several distinct concerns, which we’ll address sequentially: threats to academic integrity, the death of mastery, and the elevation of algorithms above human judgment.

First, will ChatGPT lead to an epidemic of cheating in school?

This concern is widespread with educators, not least because our current metrics for assessment–recalling facts, landing on correct answers, and summative essay writing–are all highly vulnerable to LLM abuse. Both anecdotal and qualitative evidence highlight how concerned educators are that over-reliance on AI tools could stunt development of critical thinking and writing skills, not to mention the self-reflective practices we’ve shown are crucial to student growth in prior white papers. These fears have led many schools to take strong policies preventing the use of AI generally for both students and educators.

That concern has led to a range of policies spanning secondary and higher education, ranging from abstinence to conditional acceptance. As Amanda Bickerstaff, Founder of AI for Education, noted recently after working with hundreds of district leaders across six US and Canadian states, roughly 2/3rds have adopted either a “wait and see” approach or an outright ban on GenAI. Some efforts to quantify this usage have found even more surprising statistics. A RAND corporation survey of 1,020 teachers from 239 school districts found that, as of fall 2023, only 18% of K–12 teachers reported using AI for teaching and another 15% have tried AI at least once. (RAND, 2024)

Colleges have generally been quicker to respond, but even then the guidance can offer can be confusing. Yale Admissions office, for example, refers students to a 2023 podcast on AI and College Essays in which two of their officers asserted that using chatbots at any point in the writing process, even the brainstorming stage, violates the university’s plagiarism policy. Others, like Georgia Tech, have issued more measured policies. “Tools like ChatGPT, Bard and other AI-based assistance programs are powerful and valuable tools,” they note in their undergraduate admissions site, confirming “there is a place for them in helping you generate ideas, but your ultimate submission should be your own. As with all other sources, you should not copy and paste content you did not create directly into your application.” (Georgia Tech, 2024)

Yet data suggests that AI’s effects on academic integrity may be overblown. Studies from Challenge Success, a non-profit research group affiliated with the Stanford University Graduate School of Education, revealed that, at least currently, students cheat about the same amount now that they did before GenAI tools became available. A survey of around 2,000 US students across many different demographics found that the number of students who report cheating has stayed consistent since the launch of ChatGPT: about 77% cheat about once a month. Moreover, one of the market sectors most disrupted by widely available generative AI chatbots is actually the online tutoring space, specifically companies like Chegg. Rather than paying $14.95 monthly for homework answers from such sites, students can now just ask their preferred chatbot to spell it out for them.

Revisiting our February 2023 blog post on ChatGPT’s effects on both academic work and college applications shows how much has changed and how much has stayed the same in the year since. (LeBourdais, ChatGPT, 2023) Several themes persist. Students who are compelled to cheat will always find ways to do so. Our tools for detecting generative AI use will likely always lag behind the cutting edge of LLM performance. Colleges believe that some level of human oversight is key to admissions but will likely use AI more and more to triage applications, especially given the recent surge in application volume.

Welcome your robot overlords

Interested in Artificial Intelligence? We'll match you with an expert mentor who will help you explore your next project.

How Does AI Affect the Work of College Counselors?

In a survey of 296 counselors, including independent consultants and school counselors, the college counseling company College MatchPoint found that while only 13% of respondents noticed AI-generated content in student essays, nearly 70% expected AI-based tools to be used for screening applicants. (College MatchPoint, 2024)

In fact, we actually have the first glimpse of what those screening processes might look like. A study published in October 2023 by researchers at the University of Pennsylvania explored whether artificial intelligence (AI)—of late a familiar bogeyman in conversations about college apps—could actually be used to “advance the goals of holistic admissions.” (Lira et al., 2023)

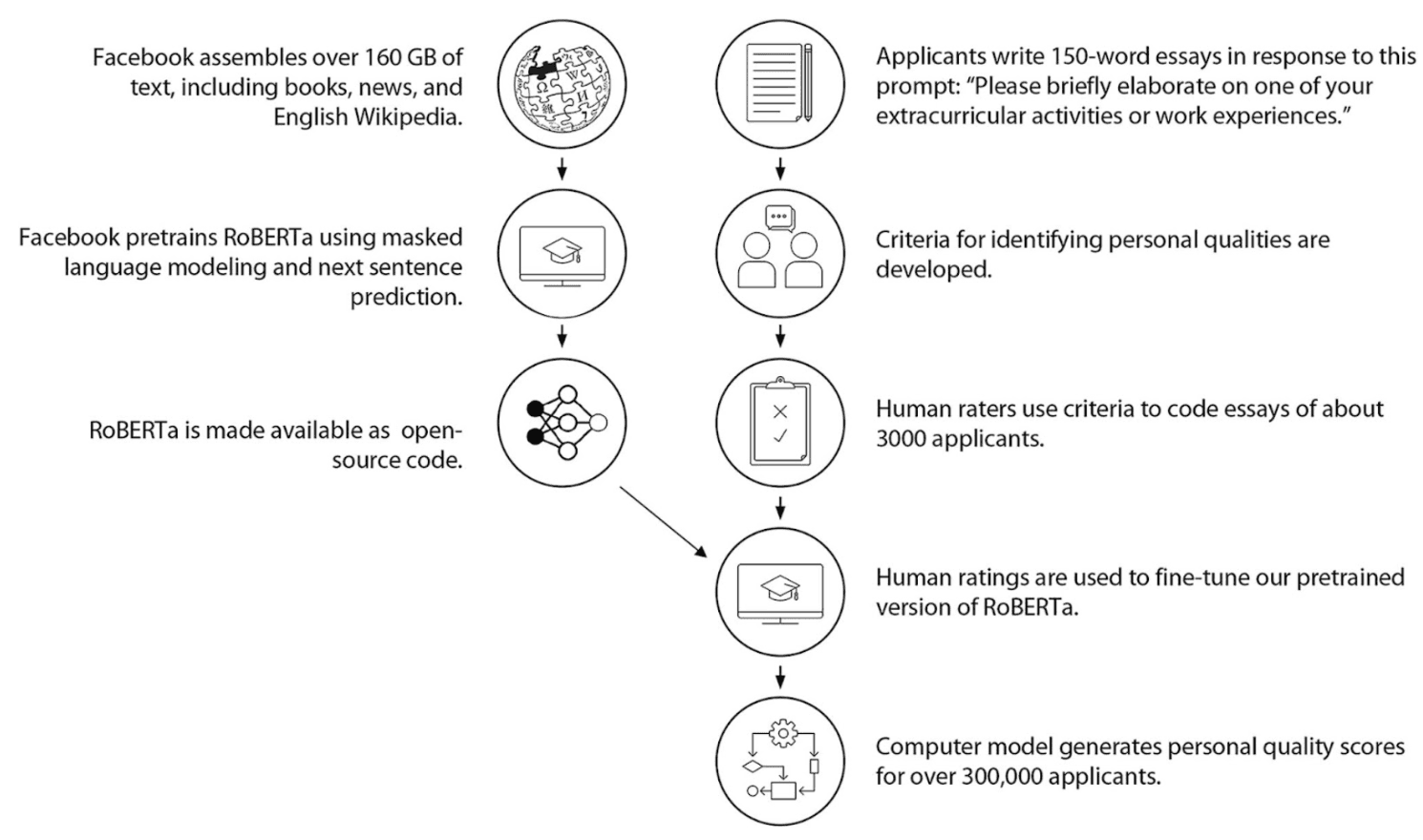

UPenn researchers trained an open-source, pre-trained AI model named RoBERTa on a rating system built by 36 college admissions officers who participated in the study. Their assessment criteria included the seven most desirable personal qualities–identified as such because they strongly predict successful graduation within 6 years of matriculation–in applicants: prosocial purpose, leadership, learning, goal pursuit, intrinsic motivation, teamwork, perseverance. Expressions of these traits were then coded into the model by manually reading and tagging more than 3,000 student essays submitted through the Common App.

The AI model was then asked to recognize these qualities in more than 306,000 de-identified student essays. The result, in lay terms, was that AI analysis correlated with human readers to an extremely high degree. Simply put, the study suggests that AI is a promising means of processing huge amounts of applications with transparent judgment criteria far more efficiently and consistently than human readers can. As more schools approach 100,000 applicants annually, AI might help to triage low from high quality candidates and perhaps even reduce the rise of waitlists and deferrals that help colleges maintain competitive yield numbers but leave students in limbo.

Of course, any innovation that places decisions about the future of individual humans into the hands of machines should be approached with the utmost caution. How concerned should students and their college counselors be about such developments, especially given that this process highlights intimate human experiences?

To begin, it’s worth remembering that these models are narrowly trained and applied algorithms and not some sentient general artificial intelligence like HAL or the Terminator who intend to lay waste to our children’s dreams. In this case, they’ve been asked to tag keywords in short essays, not render summary judgment on a student application.

More broadly, as AI researchers will tell you, any biases identified in these models stem from subjective judgments provided by human readers to begin with. In fact, AI may actually offer an advantage here. Because algorithmic models can average the opinions of specific readers into a single institutional view, such AI could make those specific human biases less determinative of admissions outcomes. Some research has revealed how strongly human subjectivity already weighs in these decision points, as when medical school applicants interviewed on rainy days receive lower ratings than those interviewed on sunny ones. (Redelmeier and Baxter, 2009) An LLM would in principle provide a fairer shot to two different applicants than they would enjoy from having two different human readers assess each of their essays (especially if they read one of those applications during a thunderstorm).

Where do Chatbots Perform Better Than Humans?

In the spring of 2023, ChatGPT had already demonstrated the ability to pass the US Medical Licensing Exam without assistance from human experts. That doesn’t mean that a chatbot will replace your physician any time soon, but more recent research from the University of San Diego found that patients actually found ChatGPT’s responses to questions to be more empathetic than human doctors, preferring the LLM’s bedside manner 79% of the time. (Ayers, 2023)

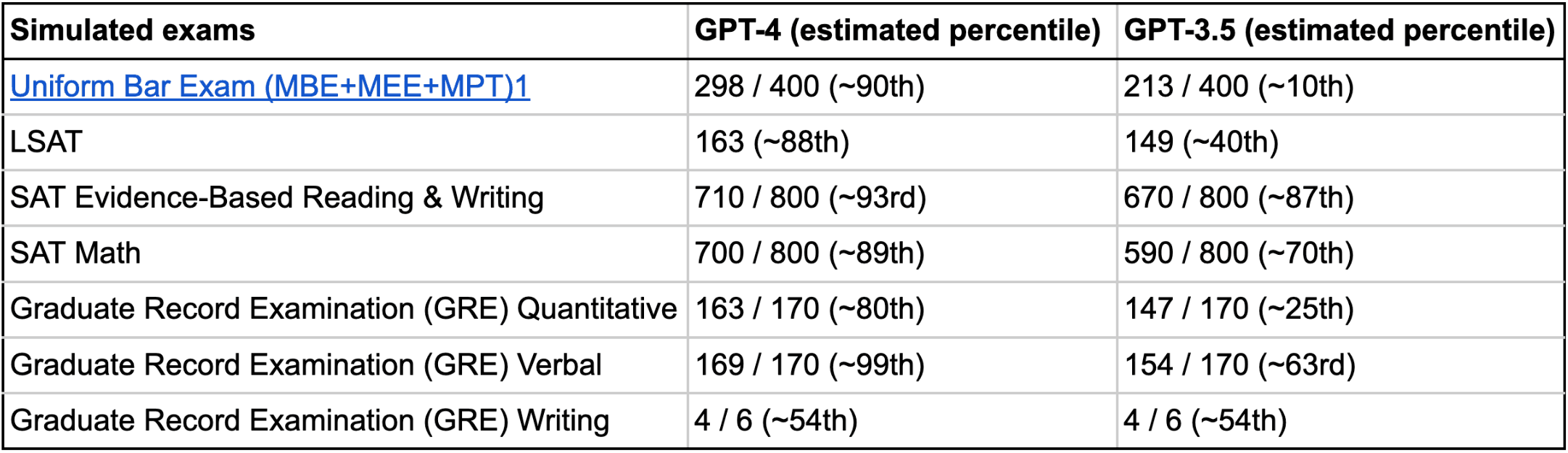

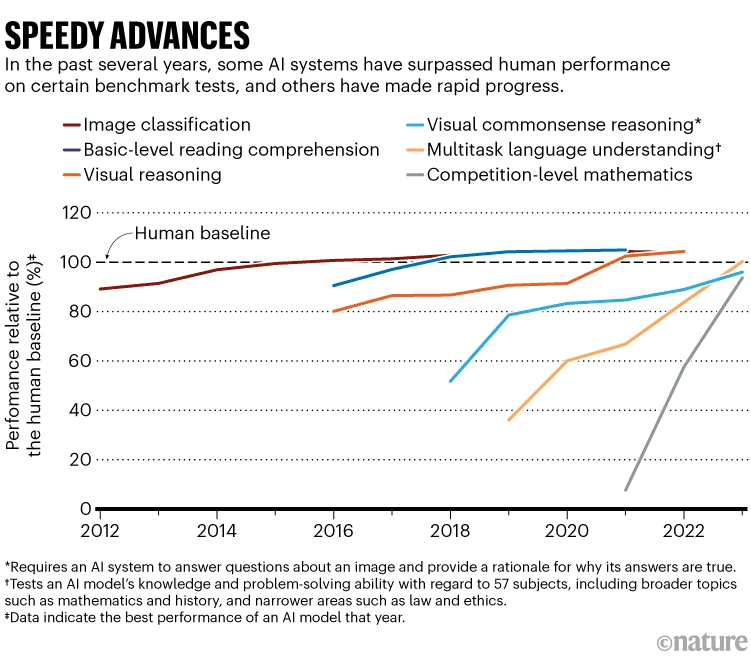

Findings like these have led to pronouncements in revered academic journals like Nature that “ChatGPT broke the Turing test.” (Biever, 2023) OpenAI’s internal research, for one, shows enormous jumps in performance on common standardized tests from GPT-3.5 to GPT-4. (OpenAI, 2023) Where the former scored in the 10th percentile on the Uniform Bar Exam, the latter reached the 90th. GPT-3.5 scored 70th percentile on SAT Math, while GPT-4 scored 89th.

Researchers have also attempted to blend performance metrics into holistic tests of LLM performance, including the Massive Multitasking Language Understanding (MMLU). A test of around 16,000 multiple choice questions across 57 academic subjects, the MMLU represents one of the best standards to compare different models across companies, but even this is already nearing the end of its utility. Google’s Gemini Ultra model recently scored 90% on the MMLU, the highest yet, leading researchers like Dan Hendrycks, an A.I. safety researcher who helped develop the MMLU, to say it “probably has another year or two of shelf life,” and will soon need to be replaced by harder tests. (Roose, 2024) The most advanced AI researchers, like those at Stanford’s Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence research lab, have proposed new indexes to help prepare for the leaps that forthcoming models will make. (Maslej et al., 2024)

How to use AI in your Teaching and Counseling Practice

For educators, the responsible reaction to the rapid development of AI tools, is that we experiment with them, both for our own work processes and so that we might prepare students to use them in the economy of their future.

“If we teach today’s student as we taught yesterday’s,” the saying from Dewey goes, “we rob them of tomorrow.”

A great example of this is Dr. Andy Van Schaack, Professor at Vanderbilt University. As Principal Senior Lecturer in the School of Engineering and Peabody College’s Department of Human and Organizational Development, Van Schaack’s research focuses on forecasting the future of technology so that we can collectively use them in evidence-based instructional practices.

If that seems a bit procedural or dry, Van Schaack’s personality is anything but. “Andy’s classes are among the largest at [the school], and he is often cited for the high degree of effectiveness of his outstanding teaching,” wrote an administrator about a prize Van Schaack won for excellence in undergraduate teaching. His lectures are lively and playful, encouraging students to ask questions about how technology might factor in their daily lives. He likes to quote John Dewey, the 20th-century educational reformer behind Progressivism, a philosophy of education that aims to cultivate problem-solving skills. “If we teach today’s student as we taught yesterday’s,” the saying from Dewey goes, “we rob them of tomorrow.”

In fact, the structure of Van Schaack’s classes essentially requires students to engage with technology to complete the most basic assignments. As the most important development to emerge in years, GenAI has taken center stage in his courses. If Yale’s admissions policy banning AI represents one end of the spectrum, then Van Schaack’s syllabi represent the other. “What if we asked students to use AI in every assignment?” he asks, “because I think we should be empowering them to use technology to achieve the same educational outcomes more efficiently.”

While this may sound daunting to more traditional educators, Van Schaack’s assignments demonstrate a mixture of established and experimental teaching methods. For instance, he quotes an Enlightenment era aphorism (often attributed to Voltaire) that we should judge someone not by the quality of their answers but the quality of their questions.

Taking this to heart, some of Van Schaack’s assignments provide students with an initial question to ChatGPT that they must then elaborate on. For instance, “Imagine you’re a professor of cognitive science and I’m one of your students. Here’s the first draft of my paper on the learning principle of interleaving. [attach or paste text] What could I do to improve this essay?” The rest of the assignment would hinge on the follow-up questions the student asks. Students must submit their follow-up questions–along with the chatbot's answers–to show their engagement with the course material and to demonstrate originality of thought.

Introductory Guideline to GenAI Prompts and Responses

For educators who want to implement AI in their teaching, some simple advice: don’t overthink it, just start by having a conversation with the LLM. Here’s a basic set of instructions on how to begin:

Give the LLM a role .

You’re an educational consultant with expertise in K-12 public schools.

You’re a high school student trying to get into an engineering college.

Give it a task.

Your task is to develop a one-page summary of a plan to incorporate AI into our school.

Your task is to make a plan to choose a rewarding series of extracurricular activities.

Ask it to ask you question.

Before you begin, ask me any questions you need in order to do a great job.

Is there anything you want to know about me before we get started?

Engage in dialogue.

The first response will almost never be exactly what you’re looking for (as with people).

Embrace the process as its own learning experience.

Polygence Scholars Are Also Passionate About

Conclusion: Individualized Learning and PolyPilot

Many educators believe AI can help us improve on the status quo of teaching and learning and could help to overcome the educational inertia that has led to an excessive focus on final grades, leaving students obsessed over getting A’s instead of actually mastering course materials. (Heaven, 2023)

Of course, there’s plenty of evidence to show that essays and tests do provide good learning outcomes, so there’s no need to throw the baby out with the bathwater. That said, AI tools could help us reimagine assignments and evaluations in such a way that students can develop more sophisticated analytical skills more quickly. Take the experience of Ross Greer, a Polygence mentor and PhD Candidate in Electrical and Computer Engineering at UC San Diego. Greer is an expert in Computer Vision and Artificial, especially in its applications to Safe Autonomous Driving. Though he works with many Polygence students on the mechanics of computer programming, Greer also wants students to take away higher-level understanding of what exactly is happening with these AI models, including how biases in the data we’ve already generated is perpetuated in LLMs.

PolyPilot: The First AI-Guided Research Program

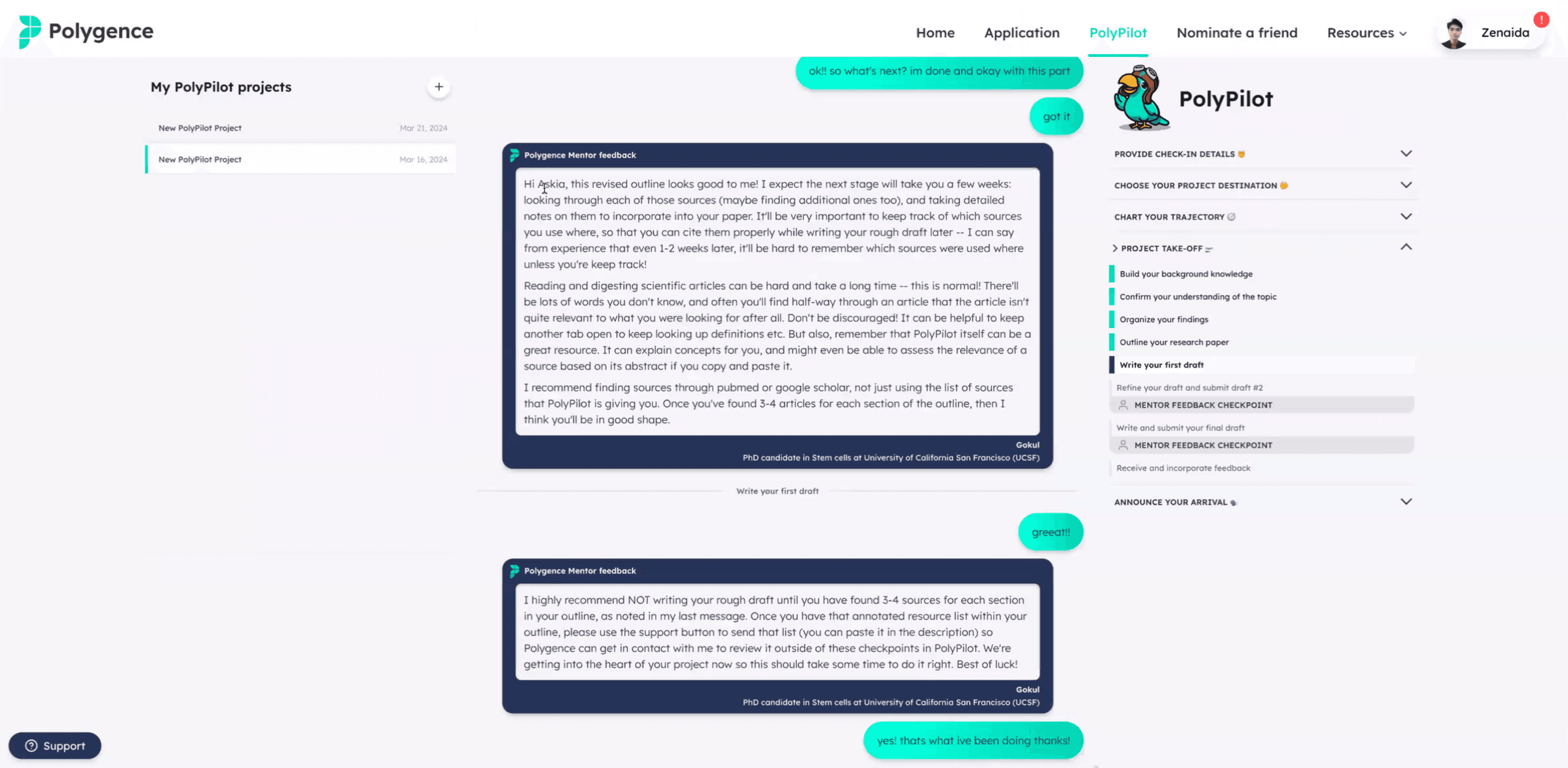

Greer’s experience as a computer scientist and teacher also helped Polygence explore new avenues for student support and growth on our platform, including the recent launch of our own AI-powered mentorship program, PolyPilot.

With insights and learnings from the thousands of projects our mentors have completed with students doing research across more than 150 different subject areas, we built an interactive research guide that helps to simplify the research journey for students. Represented as a friendly parrot, the PolyPilot chat leads students through one of the most essential research skills for academic success: literature review.

Students can ask as many questions as they wish about their research topic area, helping to build background knowledge, confirm their understanding of the topic, provide relevant resources and articles to read, and even outline their paper. The writing itself, of course, falls to the student, but they are not alone in the wilderness. Because we know real human connections rank among the most inspiring parts of our program, PolyPilot includes four checkpoints with one of our world-class mentors at key stages of the project development. This allows students to learn directly from experts in their field while still providing a much more accessible program.

There were, of course, numerous technical challenges to consider, which required not only extensive technical knowledge from our team of engineers, but also a values-based consideration about our goals for the program. Coming from a large family of moderate means in Hungary, our CEO Janos Perczel co-founded Polygence with the goal of democratizing access to research and mentorship, affording opportunities to students who like him would not normally have them. PolyPilot’s aim is to expand access to this enrichment to an even broader audience.

There are clearly many questions left to answer about such efforts, including determining their effectiveness, scalability, and relation to other academic programs. But it’s also clear that to prepare for a future of AI use in our lives and work, we must meet these challenges head on.

More Resources:

On Prompting

News and Information

Applications and Tools

NotebookLM.Google.com (apply with gmail account for early access)

Guides and Organizations

Sources

Ayers, J.W., Poliak, A., Dredze, M., et al. (2023). Comparing Physician and Artificial Intelligence Chatbot Responses to Patient Questions Posted to a Public Social Media Forum. JAMA Intern Medicine. 183(6):589–596. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2023.1838

Biever, C. (2023). ChatGPT broke the Turing test — the race is on for new ways to assess AI. Nature. 619, 686-689. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-023-02361-7

Bloom, B. S. (1954). Taxonomy of educational objectives (Prelim. ed). Longmans, Green.

College MatchPoint. (2024). NAVIGATING AI’S RISE IN COLLEGE ADMISSIONS: SURVEY OF EDUCATION CONSULTANTS AND SCHOOL COUNSELORS. https://www.collegematchpoint.com/genaicollegecounseling

Diliberti, M. et al. (2024). Using Artificial Intelligence Tools in K–12 Classrooms, RAND Corporation, RR-A956-21. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA956-21.html

Georgia Institute of Technology, Office of Undergraduate Admissions. (2024). “Application Review Process: Undergraduate Admission.” https://admission.gatech.edu/first-year/application-review.

Heaven, W. (2023). ChatGPT is going to change education, not destroy it. MIT Technology Review. https://www.technologyreview.com/2023/04/06/1071059/chatgpt-change-not-destroy-education-openai/

Klein, D. (2018). Mighty Mouse. MIT Technology Review. https://www.technologyreview.com/2018/12/19/138508/mighty-mouse/

LeBourdais, G. (2023). Great Work: Why Feedback is so Important for Students and How to Make it More Effective. Polygence White Paper. https://www.polygence.org/white-paper-great-work-why-feedback-is-so-important-for-students

LeBourdais, G. (2023). ChatGPT’s disruption of Education and College Admissions: A Tool or Cheat Code. Polygence Blog. https://www.polygence.org/blog/chatgpt-education-and-college-admissions

LeBourdais, G. (2023). New Research on the Role of AI in the College Admissions Process. Polygence Blog. https://www.polygence.org/blog/role-of-ai-in-college-admissions

LeBourdais, G. (2023). Using Google’s AI Assistant Gemini (formerly Bard) to Kickstart Your College List. Polygence Blog. https://www.polygence.org/blog/google-bard-college-list

Liang, W., et al. (2024). Monitoring AI-Modified Content at Scale: A Case Study on the Impact of ChatGPT on AI Conference Peer Reviews. arXiv.org. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2403.07183

Lira, B., et al. (2023). Using artificial intelligence to assess personal qualities in college admissions, Scientific Advances. Vol. 9, no. 41. DOI:10.1126/sciadv.adg9405

Maslej, N., Fattorini, L., Perrault, R., Parli, V., et al. (2024). The AI Index 2024 Annual Report. AI Index Steering Committee, Institute for Human-Centered AI, Stanford University. https://aiindex.stanford.edu/report/

Mollick, E. (2024). Co-intelligence : living and working with AI. Portfolio/Penguin.

OpenAI. (2023). GPT-4 Research. https://openai.com/research/gpt-4

Redelmeier, D. A., & Baxter, S. D. (2009). Holiday review. Rainy weather and medical school admission interviews. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l'Association medicale canadienne, 181(12), 933. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.091546

Roose, K. (2024). A.I. Has a Measurement Problem. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/04/15/technology/ai-models-measurement.html

Turing, A. M. (1950). Computing Machinery and Intelligence. Mind, 59 (236), 433–460. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2251299

Vaswani, A., Shazeer, N., Parmar, N., Uszkoreit, J., Jones, L., Gomez, A. N., ... & Polosukhin, I. (2017). Attention is all you need. Advances in neural information processing systems, 30.

Watters, A. (2021). Teaching machines : the history of personalized learning. The MIT Press.

Wiener, N. (1948). Cybernetics; or, Control and communications in the animal and the machine. Hermann; Technology Press.

Wooldridge, M. J. (2021). A brief history of artificial intelligence : what it is, where we are, and where we are going (First U.S. edition). Flatiron Books.