From Hong Kong to Princeton Valedictorian to Stanford Dropout to Forbes 30 Under 30

6 minute read

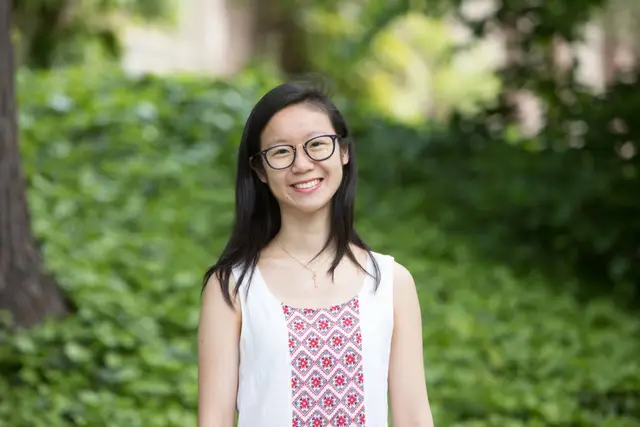

When my 28 years of existence is summed up in a 14-word title, it may seem like an extremely linear and, might I say, “impressive” journey. A lot of people ask me whether I had been working towards entrepreneurship all my life and whether the moment I’m living now is the culmination of years of focus and hard work. And a lot of people are surprised when my answer is a resounding no. What you don’t see is all the pivots and moments of epiphany (and disillusionment) in between each of those 14 words, and what I hope to do here is to give you a glimpse into the winding path that led me to where I am today and the unlikely thread that linked all of these disparate milestones together - projects.

On my wedding day on December 12, 2021, my father gave a speech that drew laughter from everyone in the audience. He characterized me as a “very laid-back child”, invoking an endearing Cantonese phrase he often used to describe the young me - “a clump of rice”. So how did I get from being a “laid-back clump of rice” to where I am today? As my father then narrated, in middle school, something clicked and I realized that learning wasn’t the boring, interminable journey that most uninspired students make it out to be, but rather, a series of self-contained projects that let me experience the world anew every time. Back in 8th grade, I had an instrumental English teacher who assigned me side projects in poetry. One such side “project” was to memorize William Blake’s poem The Tyger and to investigate its meter (if anyone’s curious, it’s written in a meter called trochaic tetrameter catalectic!). This experience opened my eyes to the power of the rhythms of language and made me fall in love with how words can be strung together to form emotionally charged tableaus. After this experience, I started to see every writing assignment, every reading packet, as infinitely repeatable ways for me to experience the power of words.

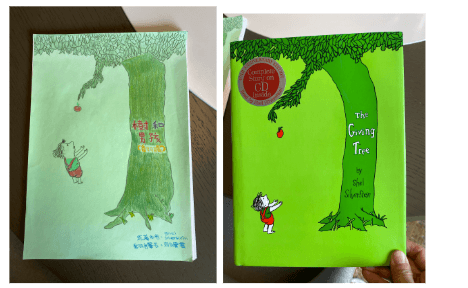

Extracurricular Translation Project

I had been learning English for a while by the time I was in middle school, and I thought to myself - why not create a project where I combine my love for the Chinese and English languages to create something personally meaningful? This thought occurred to me one month before mother’s day that year, so I decided that I would translate one of my favorite children’s books into Chinese for my mom and copy over the original illustrations (I was many things as a child, but a talented artist I was not). The book I chose was The Giving Tree by Shel Silverstein. My mother is bilingual in Chinese and English, but since her native language is Chinese, I thought it would make for an interesting reading experience for her. The book had also moved me greatly as a child, and I felt that my parents were to me, much like the tree was to the young boy - fiercely selfless and endlessly devoted.

To my chagrin, it wasn’t until much later that I found out that literary translation was a booming industry. I remember feeling slightly crushed when I learned that there already existed many different translations of this adorable book. But deep down, I still felt that my translation was special because it was mine. And strangely enough, although I could readily buy a Chinese version of The Giving Tree from any bookstore in Hong Kong, that did not detract from the intense pride I felt for having completed something from beginning to end of my own accord.

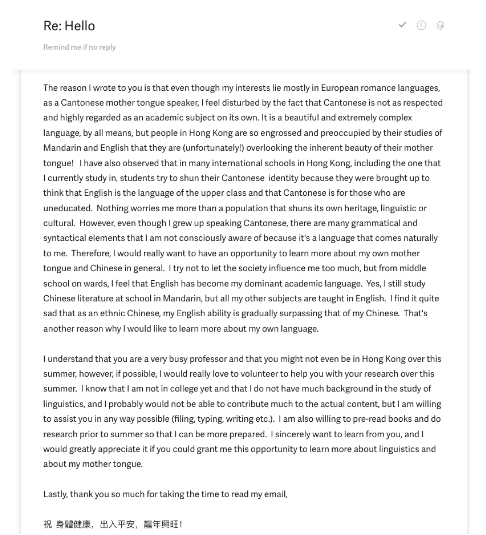

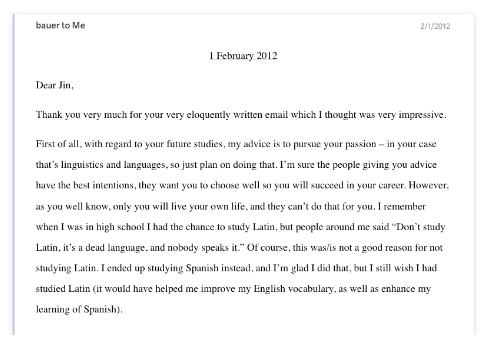

Cantonese Linguistics

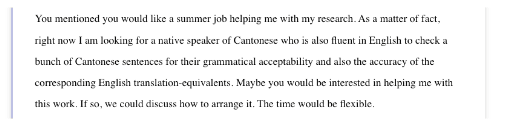

As I moved from middle school into high school, my fascination with languages only grew. I started learning French from a very strict Cambodian-French teacher who was a family friend of my grandpa’s, and started thinking a lot about how different languages can express the same meaning through drastically different orthographic and grammatical systems. When I was in 10th grade, I distinctly recall watching a news segment with my family when a linguist named Robert Bauer appeared for a short interview. He is an American linguist who devoted his life to studying Chinese (and particularly, Cantonese) linguistics, and was a professor at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University. This interview lit a fire in me - why was I spending so much time studying French and English when there are languages over which I have complete mastery - Mandarin Chinese and Cantonese - that I’ve barely thought about? This made me want to reach out to him to see if there’s any way I could get involved in his research as a native speaker of Cantonese. I spent the next couple of days drafting and redrafting my very first - and definitely not my last - cold email. I finally sent it on Sunday, January 29, 2012. You can find an excerpt of the email below:

I was floored by the fact that Professor Bauer chose not only to respond to me, but that he offered me a job to help him with his research! Over the course of the next year, we would correspond back and forth about various manuscripts he’s working on, and he would ask for my feedback and interpretations of particular Cantonese sentences and phrases that he was analyzing. Though not a formal internship by any means, this experience taught me a number of extremely valuable lessons:

Putting myself out there works! At first, I was hesitant to email him because the chances of him actually reading my message and responding seemed so abysmally low. I remember clearly what my parents said in response to my hesitancy: you miss 100% of the shots you don’t take!

Even though this took time away from my school work, it was something I truly enjoyed and cared about. Like the best kinds of research - this work gave me the opportunity to look at something as ubiquitous as my mother tongue through a completely new lens. It made me fall in love with this language I’ve spoken since I was a child, and also helped me appreciate all the ways in which it was undervalued by society.

Unlike school work, working with Professor Bauer also made me feel that I was making an actual impact in the field of Cantonese research. Though in my own small way, I was helping to democratize access to the language and contributing to the wider case that Cantonese is no less rich of a dialect than more popular languages like Mandarin or English. Most importantly, I learned that making an impact matters to me - a thread I’ll pick up on many years later.

Getting into Princeton

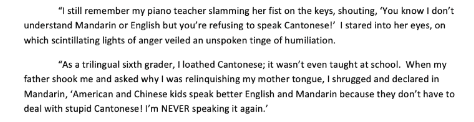

Did working on this Cantonese linguistics project help me get into Princeton? While I can’t say for sure, what I know is that what mattered most was not the content of what I worked on - but rather, how I talked about it. Colleges care deeply about a student’s authentic voice and genuine intellectual curiosity - much more so than they do about the actual research or projects that were done. To that end, my entire Common Application personal essay was about my reflections from working with Professor Bauer. In the essay, I spoke about my 180 degree transformation from refusing to speak Cantonese (yes, I went through that phase) because I felt like it was “useless” and “not even taught in school” to working with a professor on producing nuanced linguistic analyses of Cantonese syntax and semantics.

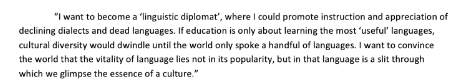

I used my research project experience as a jumping off point to reflect on my intense passion and talent for languages, and also used it to make the point that in the future, I wanted to work in “linguistic diplomacy”. The argument I made was that the best way to preserve diversity and to bridge the gap between communities is to speak the language of the other, and it was my aspiration to spearhead that movement. (Grandiose, I know!).

Thriving at Princeton

Many students have asked me: I want to be the valedictorian of my class at XYZ college - what are the steps I have to take in order to make that a reality? How did you plan out your journey to become valedictorian at Princeton?

These questions always baffled me for the simple reason that I didn’t come to Princeton aspiring to be valedictorian (in fact, I barely knew what it meant). Nor do I think that’s the best use of any freshman’s time and energy. This is how I spent my 4 years at Princeton : by being an intellectual sponge. I took classes about languages I never knew existed (a class on Old Irish, a class on Egyptian Hieroglyphs), I read voraciously (I took a class where we read 2 works of classical literature a week), I challenged myself by joining a French theater troupe, and I made some of the best friends of my life. I would be lying if I said I didn’t care about my grades, but what sustained me throughout was the pure excitement and joy of learning. My favorite time of the year was the last week of every semester, when the course catalog for the next semester would be released.

The biggest project I, along with everyone else, undertook at Princeton was my senior thesis. Coincidentally, it was another translation project where I explored a 19th century female poet’s French translations of 7th-8th century classical Chinese poems. Much like my very first hands-on translation project, this felt like a huge undertaking. It was the longest, and most independent project I had carried out to date, and I was responsible for the whole process - from time management, to planning, to writing, to getting feedback on various sections, to coordinating between different advisors… The content of what I was working on was incredibly fun, but what I took advantage of the most in my PhD a year later was what I learned about the research process.

Polygence - the biggest project yet

I graduated from Princeton in 2017 and then went straight to Stanford to start an even bigger project - my doctoral thesis. I started learning Arabic at Stanford and dove head-first into postcolonial North African French novels. I was fascinated by the interplay between the French and Arabic languages, and by the way in which language often takes on the role of a character that shapes and influences the narrative trajectory.

Fast forward to now - I’ve taken a break from my PhD to pursue a career in education and entrepreneurship. I realized that while intellectual pursuits were incredibly rewarding, I was craving work that was higher impact (something I learned from working with Professor bauer) and faster-paced. I teamed up with my long-time friend and partner-in-crime Janos Perczel to build an online platform that enables high schoolers to work on passion projects (read our founding story here). Our mission was born out of our own personal experiences - passion projects have gotten us both to where we are today. As in my case, my academic and professional journey has been a series of projects and learning experiences - each more exciting and ambitious than the last. From my first mini project of translating a children’s book to my paused project of my PhD dissertation, I’ve grown an incredible amount.

And now, what is Polygence if not for the biggest and most ambitious project I’ve ever undertaken?

Want to Learn More?

Join Polygence and do your own research project tailored towards your passions and guided by one of our expert mentors!