Boredom, Burnout, and Agency in High School Students

5 minute read

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Rates of boredom and burnout have soared among high school students

Students frequently report a lack of satisfaction, connection, or sense of accomplishment with regard to their school work

A self directed research project or engagement with independent research outside of school can be a critical tool to regaining high schoolers feeling of agency and optimism toward their futures

High schoolers face mounting mental health challenges. In recent years, students have been forced to adapt to unpredictable learning and testing environments, causing them to lose more control over their academic lives than previous generations have. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, mental health was already worsening among high schoolers. Between 2009 and 2019, persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness jumped from 26.1% to 36.7% among high school students. In 2021, a CDC survey found that 44% of high school students felt persistently sad or hopeless. With so much out of students’ control, experts in education and psychology are pointing to a desperate need to bolster students’ sense of individual agency to improve mental health outcomes.

Psychologists have consistently linked lack of perceived individual agency to increased feelings of boredom and burnout at school, both of which can lead to serious negative consequences for student wellbeing and success. While boredom and burnout have different symptoms, there is evidence that increasing individual agency in high school students through, among other strategies, self-directed projects can decrease and prevent boredom and burnout in school.

Boredom in School

In this section:

School boredom rates have been increasing since 2008.

Academic boredom can lead to serious negative consequences for students’ mental health.

Boredom can occur when a student does not feel meaningfully engaged with or personally connected to a learning activity.

Practicing mindfulness can improve autonomous motivation, which reduces boredom.

Working on self-directed projects can improve students’ individual agency, increasing academic engagement, reducing boredom, and improving mental health outcomes.

What, exactly, is boredom?

Psychologists distinguish between two types of boredom. Westgate and Wilson (2018) separate “trait boredom” — which results from a person’s disposition — from “state boredom,” which is an environmentally induced state of wanting, but not being able, to do something meaningful. While trait boredom is related to a person’s underlying proneness to boredom (and can, in some cases, be related to attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder), this second type of boredom reflects a disconnect between a person’s present situation and their interests. Put simply, state boredom indicates an underlying “desire to do something different,” like being in class but wanting to be outside. Mugon et al. write that state boredom “is a ubiquitous human experience in which individuals are motivated to engage with their environment but fail to successfully do so.” Finally, Waterschoot et al. define it as “a discrepancy between the current, meaningless situation and a desired, more meaningful situation.” For many high schoolers, one or more of these definitions will probably sound familiar.

How many high schoolers experience boredom?

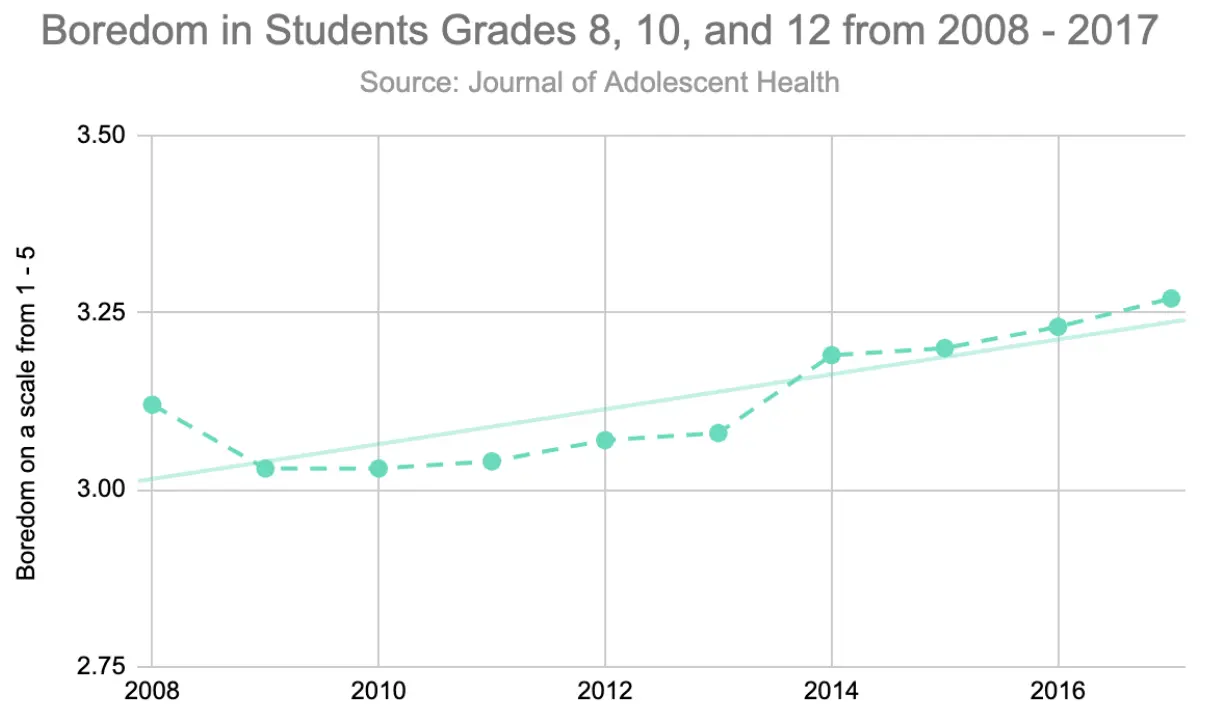

Boredom at school is increasingly common in the United States. Nearly half of high school students experience daily boredom. And, boredom can affect students of all abilities: a group of psychologists recently reported that “high boredom can occur in both low- and high-achieving students.” What’s more, a study published in the Journal of Adolescent Health discovered that rates of academic boredom have been growing among middle and high schoolers. U.S. students in grades 8, 10, and 12 reported a nearly 2% increase in boredom every year from 2008 to 2017, the most recent year included in the 2020 study. Interestingly, the researchers also found that female students were bored at earlier grade levels than males: eighth grade was the peak in boredom for females, while male students were most bored later, during tenth grade. Indeed, a previous study from 2018 by Martz et al. found that female eighth graders who identify as Black, biracial, or Indigenous American, and who live in rural communities, are the most likely students to experience frequent school boredom. As a result, people in these demographics, as well as all students who experience academic boredom, are prone to serious negative consequences.

What are the consequences of boredom in school?

Boredom in school is linked to serious negative mental health outcomes, as well as to lower career aspirations. According to Furlong et al.,

Depression, anxiety, drug or other substance addiction, and decreased quality of life are associated with frequent boredom (Chin et al., 2017). Outcomes associated with boredom and the residual effects of this emotion (either coupled with other negative states of being or not) can deplete joy, meaning, and happiness. Bored students can experience negative emotional states alongside boredom, including depression, anxiety, and apathy (van Hooft & van Hooft, 2018).

In addition to being linked to mental health concerns, frequent academic boredom can have negative effects on students’ career ambitions. In a 2019 Swiss study of 662 eleventh grade students, researchers found that being over- or under-challenged in class led to a lowering of career ambition in students with high trait boredom. That is, students who are prone to boredom and who experience either too much or too little academic challenge are less likely than their peers to aim for ambitious career paths.

What causes academic boredom?

Being in the wrong class level is not the only culprit to blame when students get bored. For some students, academic boredom can indeed occur when classes are too easy or too challenging; however, boredom can also occur when the learning activity does not feel meaningful to the student. Researchers at the University of Virginia present strong evidence that while mismatches between cognitive demand and ability contribute to boredom through non-optimal challenge, there is another, equally important factor contributing to state boredom: “meaning.” Their “MAC” (Meaning and Attentional Components) model predicts that boredom “is experienced when people feel either unable or unwilling to cognitively engage with their current activity. Put differently, to avoid boredom, people must be able to focus on an activity and want to do so, and thus experience meaningful engagement.” This is in line with the control-value model of Pekrun et al. (2010), who demonstrate that academic boredom results from activity that is either over- or under-challenging and that the student perceives as unimportant. According to these two models, school boredom occurs when classes are either too challenging or too easy, and/or when they are not perceived by the student as being meaningful or valuable to them. Switching into (or out of) a difficult class, then, may not be the solution for all bored students.

What are the solutions for students who are frequently bored?

Psychologists have identified a number of strategies to help students who are bored in school. For example, there is evidence that practicing mindfulness can help increase autonomous motivation and decrease boredom. In a study conducted during a COVID-19 lockdown, Waterschoot et al. found in 2021 that mindfulness is positively associated with autonomous motivation, and autonomous motivation actively works against boredom. “Findings,” the authors conclude, “showed that especially mindful people experienced less boredom and more life satisfaction by having a higher awareness and by deploying more autonomy-oriented strategies.” In other words, practicing mindfulness helps people to internalize their locus of control, reducing boredom. In a different paper, from 2019, psychologists found that students experienced more positive emotions (“happiness, relaxation, contentment, interest”) concurrently with high mindfulness, while negative emotions (“depression, anger, boredom, sadness”) were found alongside lower levels of mindfulness. In addition to increasing autonomous motivation through mindfulness, there is strong evidence that increasing students’ academic agency is beneficial for reducing boredom.

Do your own research through Polygence!

Polygence pairs you with an expert mentor in your area of passion. Together, you work to create a high quality research project that is uniquely your own.

Self-guided projects can help students fight boredom by increasing agency and engagement with an academic activity that is meaningful to them. According to a 2020 study from the University of Waterloo, there is a significant negative correlation between students’ perceived individual agency and their levels of boredom, and a positive relationship between perceived agency and academic success. Their results show that students who exhibited independence and self control had more academic success and experienced less boredom, overall, when compared to their peers. The authors write that “when learners feel empowered by the belief that their own actions and learning strategies have a high chance of breeding successful engagement and achievement, feelings of boredom are more likely to be kept at bay.” The study suggests that frequently bored students would benefit from active learning strategies that give them a high degree of agency. “One’s sense of self agency,” write the authors, “is likely to play a role in both self-control and boredom proneness in academic settings.” This is also in line with the MAC and control-value models of academic boredom (described above), which predict that state boredom can occur when students perceive low personal meaning in an activity. By increasing their sense of personal control over their learning, students can also increase their level of meaningful engagement, reducing boredom and increasing academic success and satisfaction.

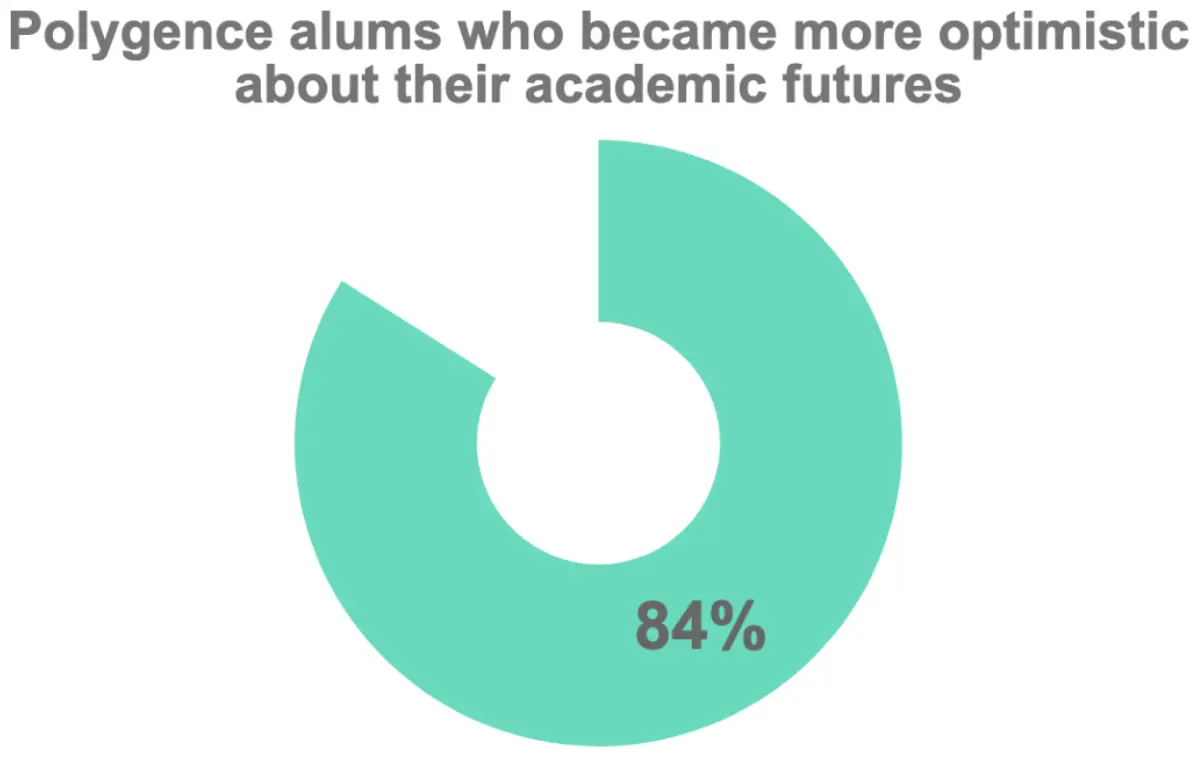

Research from Polygence reinforces the link between self-guided research or passion projects and positive outcomes for mental health and academic satisfaction. Polygence is an online research academy that empowers students through independent projects alongside one-on-one mentors. One Polygence student completed a self-guided research project, titled Coping during Covid-19, which explores the connection between internal and external locus of control and emotional coping during the COVID-19 pandemic. The results show that high school students with high individual agency (i.e. who perceived greater control over their academic and life outcomes) were better positioned to cope with the unpredictability of the pandemic. Polygence’s own post-program survey data shows that 84% of students who complete independent projects felt “more in control of their education” which, as noted above, psychologists have found to prevent feelings of boredom. Furthermore, 88% found that what they learned during their independent projects would help or have already helped them succeed in college. In 2022, the Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development recommended giving students “more autonomy in learning” and “control over their time" in response to the unpredictability that middle and high schoolers have experienced since 2020. Working on self-guided projects has become an essential component in promoting positive outcomes in wellbeing and academics among high schoolers.

Burnout in School

In this section:

Burnout is an emotional state of exhaustion, cynicism, and feelings of inadequacy.

Academic burnout is hard to measure, but up to 18% of high schoolers experience it.

Academic burnout can be detrimental to students’ physical, affective, and cognitive health.

The most common causes of school burnout are a low sense personal accomplishment and a lack of connection with and support from teachers.

Maintaining A) a positive outlook towards the future and B) a sense of personal accomplishment can counteract the feelings of inadequacy and inefficacy that contribute to school burnout.

What is school burnout, and how does it relate to boredom?

Whereas state boredom reflects a desire to do something different, burnout is an emotional state that includes exhaustion, cynicism, and feelings of inadequacy. Symptoms of school burnout can include chronic tiredness, irritability, and discontentment with school-related environments. As part of a 2021 study on burnout among high school students, Özhan et al. break down the experience of academic burnout into three components: “exhaustion at school, cynicism, and a sense of inadequacy at school… Exhaustion at school refers to burnout felt towards school and school-related work, cynicism refers to the belief that the school is not necessary or will not benefit, and inadequacy at school refers to students’ thoughts that they will not be able to achieve the tasks required by school.” So, as with boredom, a mismatch between cognitive demand and ability and, on the other hand, a lack of perceived value in learning can both be inherent to school burnout. Burnout, then, can be thought of as a severe form of chronic boredom coupled with intense exhaustion.

How many high schoolers experience burnout?

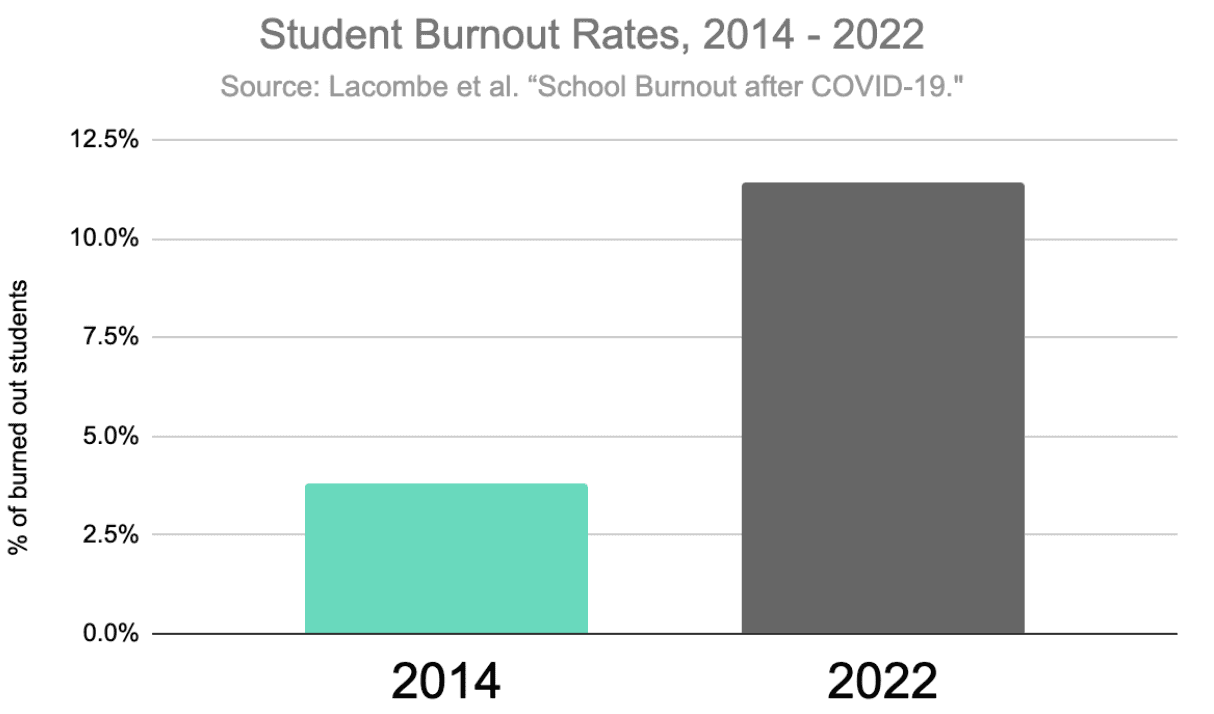

Like boredom, school burnout is on the rise. In a European study comparing student burnout data pre- and post-COVID-19, Lacombe et al. found that students today report significantly higher burnout rates than those in 2014 did. In their meta study, they found that most research from 2012 - 2021 suggested burnout rates among high school students to be between 7 and 18%. According to their own original research, including data from 2014 and 2022, three times more students reported experiencing severe burnout in the second round of measurements than in the first (3.8% in 2014 and 11.4% in 2022). These data demonstrate a significant increase in school burnout since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic — an alarming finding considering that burned out students can experience negative consequences that exceed those of bored students.

What are the consequences of school burnout?

Academic burnout can lead to grave physical and emotional consequences, not to mention academic repercussions. A 2017 study on reducing and preventing school burnout found that school-burnout syndrome shows three types of symptoms: physical, affective, and cognitive:

Physical symptoms can include chronic tiredness; decreased energy and resistance to disease; head, back, and muscle aches; and disrupted sleep patterns. Affective symptoms include insecurity, a lack of confidence about the future, constantly feeling tense and irritable, being angry and impatient, exhibiting less polite/respectful attitudes when relating with others, and developing negative attitudes towards friendship (Çimen & Ergin, 2001). Cognitively, burnout can manifest as being discontented with work, being disinclined to engage in work and work-related environments, not going to work, and developing negative attitudes and beliefs towards life and its meaning (Aslan et al., 2005).

In addition to these impacts on student wellbeing, school burnout can have adverse effects on students’ academic achievement. In a paper titled “The Effect of School Burnout on Academic Achievement and Well-Being in High School Students,” researchers found that school burnout correlates significantly and negatively with both wellbeing and academic achievement. In other words, in addition to feeling worse, students who experience high levels of burnout also tend to perform less well in school and earn lower GPAs than their non-burned-out peers. What’s more, additional evidence suggests that the negative consequences of school burnout are particularly prevalent among “students who do not seek support from their parents or other family members.” In order to better reduce and prevent school burnout, researchers are currently working to better understand its causes.

What causes burnout in school?

Psychologists have found that lack of one-on-one support from teachers, as well as a reduced perception of personal accomplishment, contribute significantly to student burnout. In 2017, a meta-analysis by Kim et al. reviewed 19 studies on middle schoolers, high schoolers, and university students. Their analysis suggests that “Burnout syndrome is likely to be prevalent among students who… become emotionally exhausted, become cynical, and feel little sense of accomplishment during their academic life.” They also revealed another significant factor: individual support from teachers. In fact, they explain that “support from the school or teacher has a stronger [negative] relationship with student burnout than parental support or peer support.” The researchers also emphasized the strength of the correlation between burnout and “diminished personal accomplishment, which occurs when a person shows a tendency to evaluate oneself negatively and a decline in a feeling of competence and efficacy.” Their results indicate that this reduced sense of personal accomplishment is a stronger predictor of burnout than either exhaustion or cynicism. Put differently, students who are hard on themselves and seldom enjoy the feeling of personal accomplishment (even if they are accomplished) or don’t have strong one-on-one connections with teachers are more likely than others to become burned out.

Are there solutions for school burnout?

Maintaining a positive outlook towards the future can be a helpful mechanism for students to reduce and prevent burnout. In a 2017 study including data from 389 high school students, researchers found that the “most important variable for preventing school burnout in high school students was observed to be attitude towards the future.” In this study, students who had positive outlooks towards the future experienced less burnout as well as greater subjective well-being which, according to the authors, “repairs the damage from [students’] experienced burnout.” In other words, maintaining positive perspectives on the future can help prevent school burnout while, at the same time, improving students’ subjective well-being and thereby helping them recover from past burnout. What’s more, data from Polygence suggests a link between one-on-one mentorship and positive thinking about the future.

A proven college admissions edge

Polygence alumni had a 89% admission rate to R1 universities in 2024. Polygence provides high schoolers with a personalized, flexible research experience proven to boost their admission odds. Get matched to a mentor now!"

High quality support from teachers and mentors in a mostly-autonomous learning environment can help prevent student burnout. Firstly, according to data from Polygence, the targeted mentorship and support that students received over the course of completing an independent project was valuable in maintaining a positive outlook towards the future. 84% of past program participants reported that their one-on-one mentor “helped them feel more optimistic about their academic future.” And, as noted above, optimism about the future can prevent and repair student burnout. Furthermore, the meta-study by Kim et al. discussed above revealed that targeted academic support is among the strongest factors in deterring student burnout.

The study suggests that a mostly autonomous academic atmosphere paired with support from a teacher or mentor (more than from a parent or peer) during moments of academic challenge is beneficial for avoiding burnout. And, quality is more important than quantity: receiving excellent, individual support during key moments of challenge while remaining mostly autonomous empowers students to feel more in control of their learning. Accordingly, the Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development recommends that “to promote student wellness, the fundamental shift should be to a more student-directed classroom…Students feel more in control of their learning when they determine what they need to do to master the goals or demonstrate their learning on assessments. They are also more engaged and less stressed.” Through self-directed learning, students can counteract the feelings of inadequacy and inefficacy that contribute to burnout.

Conclusion

School boredom and burnout are complex challenges that students are grappling with at increasing rates. Both can lead to serious negative outcomes for student wellbeing and success, with burnout being connected to particularly dangerous mental health implications. While boredom and burnout show different symptoms, psychologists have found strong evidence linking both to a lack of personal connection between the student and the learning activity. As discussed above, researchers Westgate and Wilson from the University of Virginia developed their “MAC” (Meaning and Attentional Components) model of boredom based on findings that personal meaning and engagement with a learning activity are just as important in predicting boredom as mismatches between cognitive demand and ability. Furthermore, students with low perceived individual agency tend to experience higher levels of boredom. Kim et al., meanwhile, found that lack of perceived individual agency and lack of high quality support from teachers also correlate with student burnout.

Data from recent psychology research shows that the more students perceive individual agency and accomplishment in themselves, the less likely they are to experience the challenges to wellbeing and academic success associated with boredom and burnout. Solutions exist for high school students at risk of boredom and burnout to improve their sense of agency and accomplishment through practicing mindfulness, maintaining a positive outlook on the future, and conducting independent projects with targeted support from one-on-one mentors, such as through Polygence.

Sources

Aypay, Ayşe. “A Positive Model for Reducing and Preventing School Burnout in High School Students.” Educational Sciences: Theory and Practice 17 (August 2017): 1345–1359. http://dx.doi.org/10.12738/estp.2017.4.0173

Center for Disease Control. “New CDC data illuminate youth mental health threats during the COVID-19 pandemic.” March 31, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/2022/2021-ABES-findings-press-release.html.

—. “Mental Health Among Adolescents.” Accessed March 27, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/docs/factsheets/dash-mental-health.pdf.

Furlong, Michael James, Douglas C. Smith, Tina Springer, and Erin Dowdy. “Bored with school! Bored with life? Well-being characteristics associated with a school boredom mindset.” Journal of Positive School Psychology 5, no. 1 (April 2021): 42-64. http://dx.doi.org/10.47602/jpsp.v5i1.261.

Golubchik, Pavel, Iris Manor, Gal Shoval, and Abraham Weizman. “Levels of Proneness to Boredom in Children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder On and Off Methylphenidate Treatment.” Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology 30, no. 3 (April 2020): 173-176. http://doi.org/10.1089/cap.2019.0151.

Kim, Boram, Song Min Lee, and Joungwha Lee. “Relationships between social support and student burnout: A meta-analytic approach.” Stress and Health 34, no. 1 (February 2018): 127-134. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2771.

Krannich, Maike, Thomas Goetz, Anastasiya A. Lipnevich, Madeleine Bieg, Anna-Lena Roos, Eva S. Becker, Vinzenz Morger. “Being over- or underchallenged in class: Effects on students’ career aspirations via academic self-concept and boredom.” Learning and Individual Differences, 69 (2019): 206–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2018.10.004.

Lacombe, Noémie, Maryelle Hey, Verena Hofmann, Céline Pagnotta, and Myriam Squillaci. “School Burnout after COVID-19, Prevalence and Role of Different Risk and Protective Factors in Preteen Students.” Children 10, no. 5 (May 2023): 823. https://doi.org/10.3390%2Fchildren10050823.

LeBourdais, GP. “Can Research Programs Improve Mental Health Outcomes for Students?” Accessed March 27, 2024. https://www.polygence.org/blog/research-projects-mental-health.

Martz, Meghan E., John E. Schulenberg, and Deborah D. Kloska.”“I Am So Bored!”: Prevalence Rates and Sociodemographic and Contextual Correlates of High Boredom Among American Adolescents.” Youth and Society 50, no. 5 (July 2018): 688-710. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X15626624.

Mugon, Jhotisha, James Boylan, and James Danckert. “Boredom Proneness and Self-Control as Unique Risk Factors in Achievement Settings.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 23 (December 2020). http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17239116.

Özhan, Mehmet Bugra and Galip Yüksel. “The Effect of School Burnout on Academic Achievement and Well-Being in High School Students: A Holistic Model Proposal.” International Journal of Contemporary Educational Research 8, no. 1 (March 2021): 145-162. https://doi.org/10.33200/ijcer.824488.

Pascoe, Michaela C., Sarah E. Hetrick, and Alexandra G. Parker. “The impact of stress on students in secondary school and higher education.” International Journal of Adolescence and Youth 25, no. 1 (2020): 104-112. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2019.1596823.

Pekrun, Reinhard, Thomas Goetz, Lia M. Daniels, Robert H. Stupnisky. “Boredom in Achievement Settings: Exploring Control- Value Antecedents and Performance Outcomes of a Neglected Emotion.” Journal of Educational Psychology 102, no. 3 (2010): 531-549. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/a0019243.

Schwartze, Manuel M, Anne C. Frenzel, Thomas Goetz, Anton K.G. Marx, Corinna Reck, Reinhard Pekrun, and Daniel Fiedler. “Excessive boredom among adolescents: A comparison between low and high achievers.” Plos One. Published November 5, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0241671.

Vatterott, Cathy. “Lessons on Student Well-Being From ‘The Great Resignation.’” Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, July 2022. https://www.ascd.org/el/articles/lessons-on-student-well-being-from-the-great-resignation

Wang, Isabel. “Coping During Covid-19: A Study on How Locus of Control Influences Coping Response in an Uncontrollable Situation.” Accessed March 27, 2024. https://www.polygence.org/projects/high-school-research-project-LOC-coping.

Waterschoot, Joachim, Jolene Van der Kaap-Deeder, Sofie Morbée, Bart Soenens, and Maarten Vansteenkiste. “‘How to unlock myself from boredom?’” The role of mindfulness and a dual awareness- and action-oriented pathway during the COVID-19 lockdown.” Personality and Individual Differences 175 (June 2011). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.110729.

Westgate, Erin C. and Timothy D. Wilson. “Boring Thoughts and Bored Minds: The MAC Model of Boredom and Cognitive Engagement.” Psychological Review, 125(5), 689–713. https://doi.org/10.1037/rev0000097.

Weybright, Elizabeth H., John Schulenberg, Linda L. Caldwell. “More Bored Today Than Yesterday? National Trends in Adolescent Boredom From 2008 to 2017.” Journal of Adolescent Health 66, no. 3 (March 2020): 360-365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.09.021.

Xu, Ding, Jiaxuan Du, Yuyang Zhou, Yuanyuan An, Wei Xu, and Ning Zhang. “State mindfulness, rumination, and emotions in daily life: An ambulatory assessment study.” Asian Journal of Psychology 22, no. 4 (December 2019): 369-377. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajsp.12383.